According to the archeological dating of the Morocco Jebel Irhoud animal fossils and the Homo sapiens who ate them, humans have hunted game animals for over 300,000 years. Although humans are omnivores, they did not start farming until 23,000 years ago, according to the Ohalo II archaeological site in Israel. This means that humans needed to hunt for 277,000 years for food security.

Kelly Maher, an avid Coloradan hunter and mother, said part of her family ethic is “we hunt to eat and we eat what we hunt.” During the Covid 19 shutdown, her family ate deer meat stored in the freezer from the previous hunting season. Maher said she believes hunting is a core part of “understanding our place in the world.”

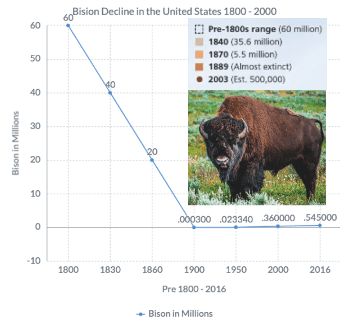

Data from All About Bison. https://allaboutbison.com/national-mammal/

American wildlife suffered at the end of the nineteenth century from mismanagement, according to the Audubon Society. The bison population had diminished from 60 million to 300 in 100 years due to lack of management and overhunting according to All About Bison. Together, President Theodore Roosevelt, George Bird Grinnell and John Muir along with the Audubon Society, established a conservation movement to preserve nature.

Roosevelt, the “conservation president,” used his authority in 1906 to protect public lands and wildlife by creating the United States Forest Service (USFS). This service established 150 national forests and 18 national monuments through the American Antiquities Act. This act protected over 230 million acres of open public space for citizens of the United States use.

With the advent of city living, increased public criticism, and reduced barriers to food security, hunting has declined in the United States. The decline of hunters is problematic state-wide for wildlife conservation efforts that depend on funding from hunting license sales.

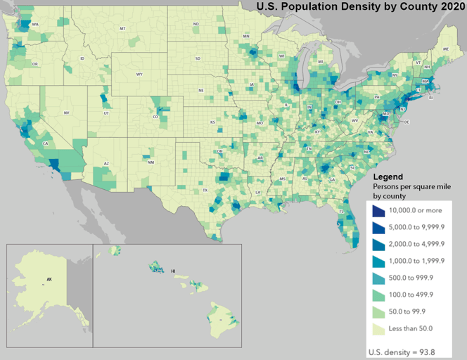

Source: 2020 U.S. Census Demographic – City density

According to Wildlife for All, between 1960 and 2020, hunting license sales increased by 2 million or 13.5 percent. The U.S. Census Bureau (USCB) reports that the population increased by 152 million or 84 percent. Although the number of hunters increased, it dropped from 7.8 percent of the population in 1960 to 4.8 percent in 2024.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service manages nationwide conservation funding through the collection of hunting license revenue and firearms and ammunition excise sales tax from each state. The funding is distributed back to the state parks and wildlife departments that manage public land conservation and animal populations.

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau. Wildlife for All. U.S Fish and Wild Life Service Hunting licenses issued between 1960 and 2020 compared to the U.S. population.

“There are 180 hunting units that Colorado has divided into Game Management Units (GMUs),” Cody Heneghan, a hunt planner for Colorado Parks and Wildlife said. “These units designate which part of the state your particular license permits you to hunt in.”

Hunting licenses for Colorado’s Western GMUs with higher elk populations are in high demand with a limited number available per year. A hunter must apply for these types of licenses through a “big game draw,” or purchase a leftover license after the draw if one is available.

“I’m not hunting as much now because the last time I bought a license, it was in a unit with a low population and I didn’t get an elk that time,” Wally Light, a 21-year-old hunter said. “It was a lot of work without a payoff. It didn’t seem worth it.” According to Colorado Parks and Wildlife, the Federal Bureau of Land Management (BLM) manages 8 million acres of public land in Colorado. However, non of the 23,000 acres of open space and trails in rural Pitkin County are open for hunting. Open space hunting in Pitkin County Colorado is prohibited according to the Pitkin County Open Space and Trails program. However, private land is huntable with permission.

But private land is diminishing. In January, Pitkin County Open Space and Trails Board voted unanimously to purchase 650 acres of private land in upper Snowmass Creek Valley to reclassify it to BLM open space.

According to wildlife advocates, limiting hunting units in Colorado become problematic for wildlife management. “Management of ecosystems is important,” Maher said. “By virtue of the fact that humans are here, we must manage this system” to ensure the well-being of animals and the environment.

Between 1970 and 2000, hunting license sales revenue increased from $600 million to $1.1 billion according to The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service reports. However, revenue remained stagnant over the next two decades.

Sources: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Congressional Research Service. Hunting license sales revenue and federal excise tax collected equally $2.2 billion in 2024.

Data from the Congressional Research Service reports that between 2017 and 2022, excise tax collected from the sale of firearms increased from $600 million (inflation adjusted) to $1.1 billion due to increased sales during the pandemic but not to sales for hunting equipment. However, funding from the U.S. Congress has decreased since 2015.

Hunting is an integral part of maintaining a stable deer and elk population. Lands maintained by hunting license revenues distributed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service are more likely to support natural wildlife.

The “availability of food sources in the wilderness is a factor in monitoring the population,” wildlife advocate Mark Surls said. This becomes a closed-loop, sustainable ecosystem.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service operating budget, is partially funded through congressional appropriations. In 2024, the operating budget was $4.1 billion with $1.722 billion allocated by the government and the balance coming from grants, excise tax revenue and hunting license sales.

Sources: Congressional Research Service Funding requested to manage Fish and Wildlife Services, and congressional funding enacted to finance conservation in all 50 states and 16 territories.

Public opinion contributes to the hunter’s image in the U.S. On Nov. 5, voters were given a choice through “Cats Aren’t Trophies” Proposition 127 to decide whether Colorado Parks and Wildlife would continue to manage the mountain lion population by issuing hunting licenses.

“Hunting deer is fair chase,” wildlife advocate Carol Monaco said. But hound hunting “mountain lion is cruel.” It isn’t helping anyone and “very few big cats are dressed for consumption. We need to learn to coexist with wildlife.”

Surls advocates that hound hunting is unethical and should be removed from the hunting license options because “it gives our hunters a bad name for violations of fair chase,” integrity in hunting.

Some critics combine hunting for food with “trophy hunting.” Trophy hunting is hunting wild animals for sport and keeping body parts for display, not food. Mesa County Commissioner Cody Davis commented that this type of rhetoric is needless with an “end route to limit hunting” and “trophy hunting is already illegal in Colorado.”

Proposition 127 aimed to remove mountain lion population management from the Colorado Parks and Wildlife. In Nov. 290,000 voters rejected the proposition. In a compromising effort at a public engagement meeting critics of mountain lion hunting demanded that “guaranteed kill” be removed from hunting outfitter’s advertising because it is illegal in Colorado and a violation of CPW’s policy.

Source: Ballotpedia Colorado Proposition 127 to Prohibit Hunting of Mountain Lion was rejected by Colorado voters, allowing Colorado Parks and Wildlife to continue managing the population.

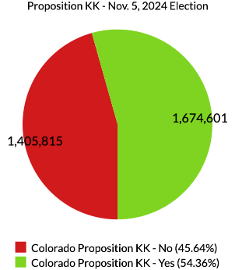

Source: Ballotpedia. Colorado Proposition KK, Excise Tax on Firearms was passed by Colorado voters, adding 6.5% excise tax to firearms and ammunition sales.

“We want to work with Colorado Parks and Wildlife,” Monaco said, “in every way so they can do their job” managing wildlife population.

As hunting license sales decrease, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service funding must be replaced with a new source. Hunting licenses are an important source of revenue.

“Colorado Parks and Wildlife are brilliant at managing the wildlife population and it should stay that way. It is a scientific method of conservation,” Davis said